By Allen Smith, J.D.

August 8, 2018 - SHRM

As smartphones have become common, employees are recording work conversations without employers' knowledge or permission in preparation for discrimination, sexual harassment and whistle-blower lawsuits. These recorded conversations have included talks with co-workers, meetings with supervisors, and even discussions with HR and executives. State and federal laws limit employers' ability to prohibit recordings, but the Trump administration has loosened federal restrictions.

"A recording of sexual harassment or a discriminatory comment can be very powerful evidence and damaging to the employer," said Jay Holland, an attorney with Joseph Greenwald & Laake in Greenbelt, Md.

Marc Katz, an attorney with DLA Piper in Dallas, said plaintiffs' lawyers now arm employees with the buzzwords needed to spark discrimination cases and send workers into businesses to record conversations that support their upcoming lawsuits. "I've been practicing for 24 years and did not see recording like this years ago. Now it's relatively commonplace," he said.

In one recent whistle-blower lawsuit, an employee surreptitiously used a pen with a tiny digital voice recorder for more than a year. Another whistle-blower in the same lawsuit compiled recordings for eight months.

Secret recordings are "definitely on the increase," not only in whistle-blower cases but also under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and in retaliation cases, said Edward Ellis, an attorney with Littler in Philadelphia. Such recordings frequently arise in sexual-harassment cases, where an employee will try to use a recorded statement as a smoking gun, he noted.

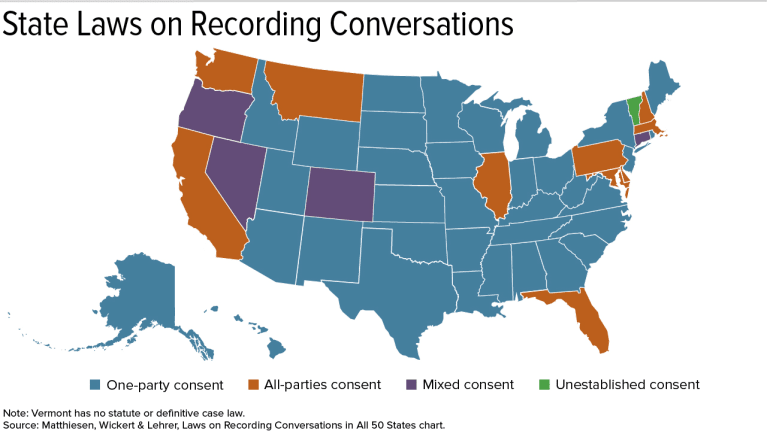

One-Party vs. All-Party Consent

Most states permit one-party rather than all-party

consent for recordings. Some debate which states are one-party and

which are all-party consent (see this chart vs. this one, for example).

One-party states require only the consent of one participant to the communication. So if the person recording is consenting and a part of the communication, that is enough. "This can lead to supervisors, managers and executives being secretly recorded without their knowledge," said Rachel Conn, an attorney with Nixon Peabody in San Francisco. "Clearly employers in all-party states have greater rights to prohibit recordings because supervisors, managers and executives cannot be [lawfully] secretly recorded" there.

Companies ought to prohibit taping no matter what state they're in, Ellis said, though such a policy will be more difficult to enforce in a state that permits one-party consent.

Employers should prohibit recording, not only to strengthen its defenses in litigation, he said, but also because recording can inhibit people from speaking freely about work and strain relationships among co-workers.

What's Allowed Under NLRA? That Depends on Who You Ask

Peter Robb, the National Labor Relations Board's (NLRB's) general counsel, stated in a June 6 memo that no-recording rules generally are allowed under the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA). The memo quotes from the dissent in an NLRB ruling, Whole Foods Market, where the board struck down a rule that employees may not record conversations, phone calls, images or company meetings with any recording device without prior approval.

"Although the board found this rule unlawful under Lutheran Heritage, Chairman [Philip] Miscimarra in dissent argued that the rule was lawful," the memo states. The NLRB overturned Lutheran Heritage at the end of last year in Boeing, which found that no-photography rules generally are permissible. Similarly, no-recording rules usually should be allowed, the memo states.

The memo clarifies that rules limiting recording and photo-taking generally are going to pass muster under the NLRA, said Mark Kisicki, an attorney with Ogletree Deakins in Phoenix. He said that he always recommends including such policies in employee handbooks.

But while Robb's memo highlights the NLRB dissent in

Whole Foods Market, the 2nd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the NLRB's

pronouncement that the grocery chain's rule was unlawful. Holland explained

that in Whole Foods Market, the NLRB concluded that using recording

devices can constitute protected activity under the NLRA for the following

purposes:

Any rule prohibiting the use of recording devices by employees should clarify that recording, whether audio or video, is permitted to address specific grievances or other areas of concern, such as safety issues, and is not intended to chill employees' exercise of their rights under the NLRA, said Lisa Cassilly, an attorney with Alston & Bird in Atlanta and New York City.

Other Governmental Positions

The Department of Labor has held that recording workplace conversations as evidence of potential radiation contamination and other workplace safety issues was protected whistle-blowing activity under the Energy Reorganization Act, which protects employees who disclose concerns about nuclear safety, Cassilly noted.

She added that the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) may take issue with broad no-recording policies that do not make an exception for evidence gathered for whistle-blowing purposes. The SEC has not yet weighed in on whether strong no-recording policies violate whistle-blower protection laws.

But it has issued a rule that confidentiality agreements must make clear that they do not cover communications with government authorities; employers that don't make this distinction risk running afoul of SEC Rule 21F-17. This rule prohibits any policies that may impede whistle-blower communications with the government.

Public-Relations Risks

Even if an employer is in an all-party consent state, there still is the risk that an employee will record bad behavior in the workplace.

"Once the proverbial bell is rung, it is hard to 'unring' it," said Anne Cherry Barnett, an attorney with Polsinelli in Los Angeles and San Francisco. A recording "could be leaked online and create a viral public-relations nightmare for an employer."

Katz said that legal cases involving secret recordings in the workplace are "not a fully developed area of the law" and predicted that they will get increased attention as secret recordings increase.